Bear it aloft, O roaring flame!

Skyward aloft, where all may see.

Slaves of the world! our cause is the same;

One is the immemorial shame;

One is the struggle, and in One name—

Manhood — we battle to set men free.

Written In Red, Voltairine de Cleyre

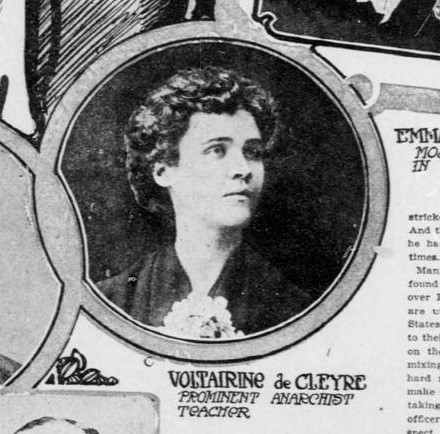

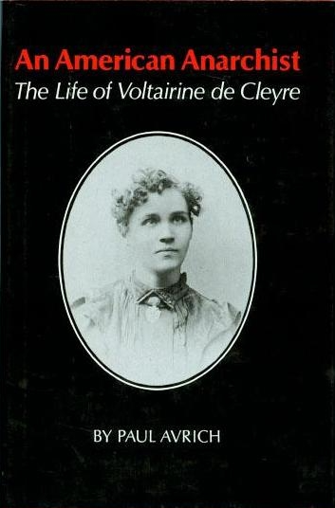

In 1986, distinguished historian Paul Avrich (1931 – 2006) donated to the Library of Congress his extensive collection of books, pamphlets, periodicals, manuscripts, and ephemera relating to his study of anarchism in Russia and the United States. Nestled among the books in his multi-format benefaction was a copy of a biography that he wrote about a member of the American labor movement, Voltairine de Cleyre (1866 – 1912), whose energetic contribution to the complexity of labor history had been all but forgotten.

Published in 1978, Avrich’s An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre renewed public interest in de Cleyre, about whom nothing substantial had been written since 1932. Nevertheless, the biographee remains largely unknown despite her direct engagement with many prominent authors and thinkers of her own and previous eras. In his forward, Avrich refers to de Cleyre as “one of the most interesting if neglected figures in the history of American radicalism.” This blog post hopes to remedy the neglect by sharing some of the interesting details of de Cleyre’s life.

A fearless feminist, an inventive poet, a dedicated teacher, and an effective social organizer, Voltairine de Cleyre’s fierce spirit emerged from humble beginnings. Voltairine (named after the French philosopher Voltaire) was known from an early age to be intelligent, headstrong, private, emotional, and stubborn. Her mother was raised by American abolitionists, and her father, a socialist in his politics, was a French émigré to the United States after the French Revolution of 1848. Both parents in this working-class family struggled to find employment, and, as a result, the family often lived in poverty.

When she was about thirteen years old, de Cleyre was enrolled in a Canadian convent school in hopes that the stringent atmosphere would instill a sense of discipline in the vibrant young woman. According to Avrich, the requirement of total obedience had a life-long impact upon de Cleyre, who developed “a generalized hatred of authority and obscurantism in all their manifestations.” Upon leaving the convent at the age of seventeen, de Cleyre subscribed to a freethought epistemology, but her philosophical views evolved over time, and, eventually, de Cleyre began to see her personal struggle for freedom from religion as being connected to a larger, common human struggle for social liberation. By the 1890s, she had moved away from freethought towards a particular understanding of anarchism that prioritized the freedom of an individual and the right to personal property.

De Cleyre’s name and beliefs became well-known among radical circles. Beginning in the 1880’s, she wrote engaging poetry and essays for progressive newspapers and magazines, and she penned eloquent speeches that she presented throughout the Midwest. She often wrote and spoke about thinkers that influenced her—Thomas Paine, Henry David Thoreau, Lord Byron, early women’s rights advocates like Mary Wollstonecraft, and contemporary figures such as Clarence Darrow and Eugene Debs.

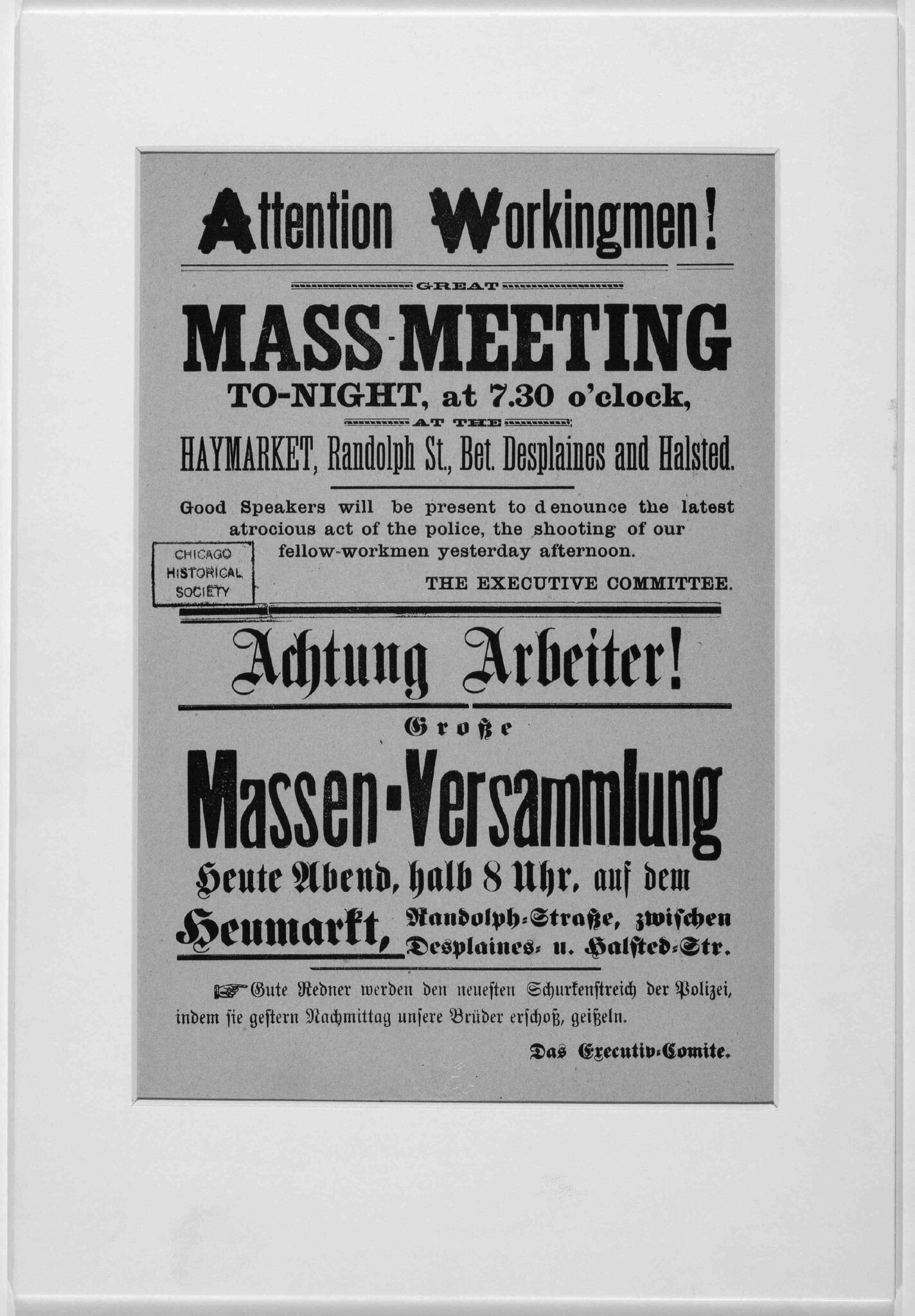

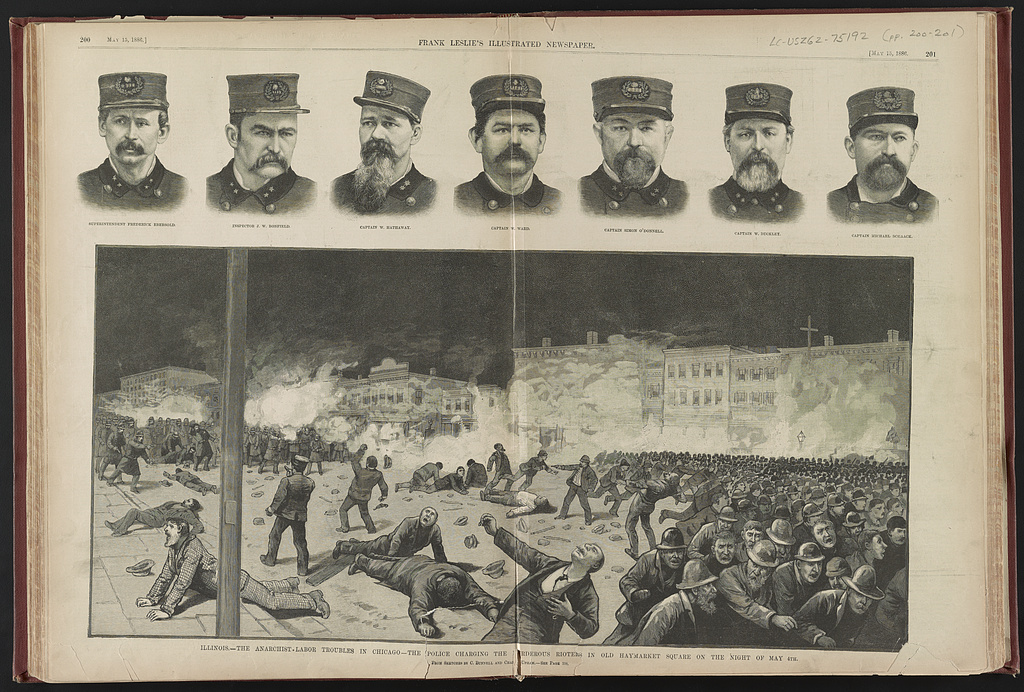

The turning point in de Cleyre’s developing convictions toward her particular form of anarchism was the Haymarket Affair. The 1880s saw significant labor organization and demonstrations, some of which focused on pushing for the 8-hour work day. One such demonstration—now infamous in labor history—took place in Chicago on May 4th, 1886, when a bomb was detonated after police disbanded a meeting of labor activists near Haymarket Square.

One police officer was killed by the explosion, and several men, both strikers and police officers, died or were wounded in the ensuing violence. Although the person who set off the bomb was never identified, four alleged anarchist labor leaders were convicted of conspiracy to commit murder and hanged. Three more men remained imprisoned until they were pardoned by Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld in 1893.

This event impacted de Cleyre profoundly, solidified her convictions, and animated her commitment to the labor movement. From 1889 to 1910, de Cleyre lived among poor Jewish immigrants in Philadelphia, where she learned Yiddish and taught English and music. She lived by the scarcest means, sending as much money home to her mother as she could, living herself in abject poverty, and was often sick from a lifelong but indeterminate illness.

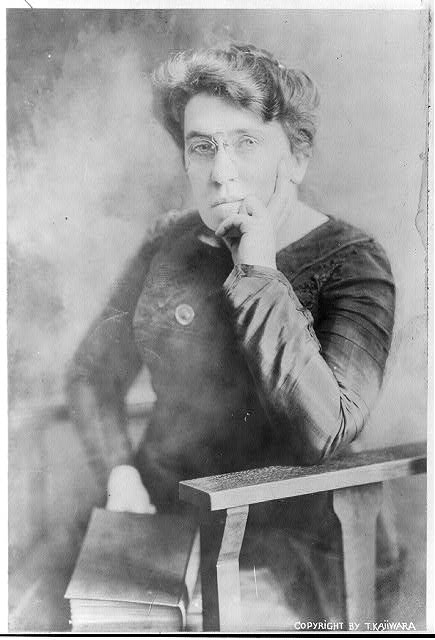

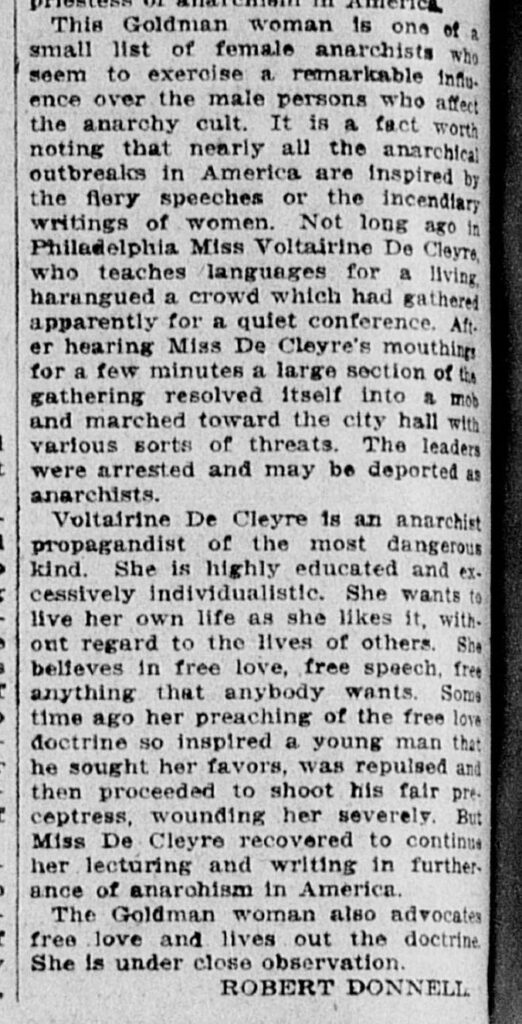

Despite exhaustion and illness, de Cleyre remained a prolific author and organizer. In 1892 she founded a social group called the Ladies’ Liberal League, an important forum for radical and feminist activity, where women were able to discuss and debate topics relating to political philosophy. One attendee at these meetings was fellow anarchist, Emma Goldman (1869 – 1940). Goldman and de Cleyre, while espousing different ideas about anarchism, were nonetheless often lumped together by the press and the public as “lady anarchists” or “lady reds.”

Goldman and de Cleyre maintained a lifelong friendship and respect for one another even though their beliefs differed greatly. de Cleyre explained these differences succinctly in her 1894 essay In Defense of Emma Goldmann and the Right of Expropriation:

Miss Goldmann is a communist; I am an individualist. She wishes to destroy the right of property, I wish to assert it. … But whether she or I be right, or both of us be wrong, of one thing I am sure; the spirit which animates EMMA GOLDMAN is the only one which will emancipate the slave from his slavery, the tyrant from his tyranny — the spirit which is willing to dare and suffer.

Despite their philosophical disagreements, it was Emma Goldman who, after de Cleyre’s untimely death in 1912, was the first to publish a selection of de Cleyre’s works. While the two women were often partnered in the public eye erroneously during their lives, only Goldman remains well-known today.

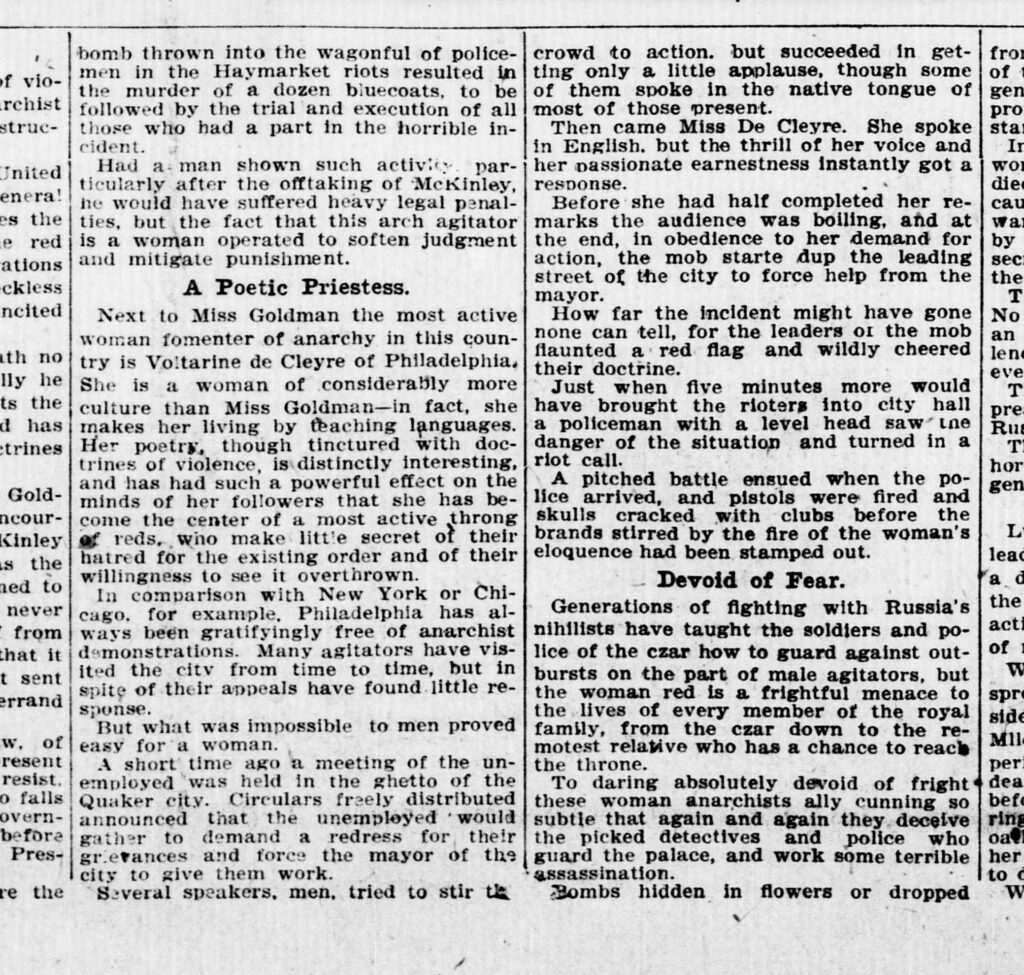

This lack of recognition may be because de Cleyre did not seek-out publicity, and she appeared in popular new outlets (rather than specialized journals) far less often than more well-known anarchists. A search of Chronicling America, for example, indicates that “Voltairine de Cleyre” appeared in the news mostly in 1902 and 1908 following particularly sensational events in her life—such as an assassination attempt by a former pupil or an arrest for inciting a riot in 1908 when she spoke at a labor rally.

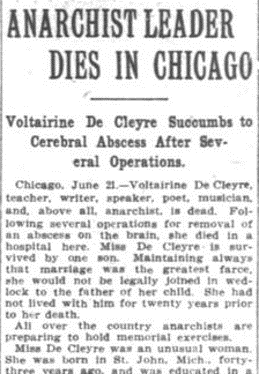

Little-known today, de Cleyre was popular at the time of her death, and more than 2,000 people attended her funeral including “Haymarket Widow” Lucy Parsons (1851 – 1942), who arranged red carnations on her casket. de Cleyre was laid to rest at Waldheim Cemetery next to the tomb of the Haymarket martyrs whose sacrifice influenced her life and work. When Emma Goldman returned to Chicago from a lecture tour, she immediately went to lay flowers at de Cleyre’s grave, and famously expressed that the Haymarket martyrs had gained another member.

Contemporaries self-published small works in honor of de Cleyre after she passed, and she was mentioned some in the press. However, she quickly fell from public awareness. Emma Goldman’s publication included introductions and a biographical sketch written by fellow anarchists Alexander Berkman (1870 – 1936) and Hippolyte Havel (1871 – 1950), but between this publication in 1914 and the 1970s, just one other work about de Cleyre was published in 1932, and that was a tribute to de Cleyre by Goldman herself.

Paul Avrich studied de Cleyre’s correspondence with friends, family, and contemporaries to write her full-length biography in 1978. This publication was the first opportunity for the public to learn about the details of de Cleyre’s personal life and build a picture of the woman behind the essays, poems, and rousing speeches that were delivered at a pivotal period in the history of the labor movement in the United States. For more information on Voltairine de Cleyre or the Paul Avrich Collection, see the resources below or contact the reference staff through Ask-A-Librarian.

RESOURCES

Haymarket Affair: Topics in Chronicling America. https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-haymarket-affair.

Paul Avrich Collection, Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress. https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.rbc/eadrbc.rb018002.

Voltairine De Cleyre Papers, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center), https://findingaids.lib.umich.edu/catalog/umich-scl-decleyre.

FURTHER READING

DeLamotte, Eugenia C., Gates of Freedom : Voltairine de Cleyre and the Revolution of the Mind : With selections from her Writing. Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2004].

DeLamotte, Eugenia. “Refashioning the Mind: The Revolutionary Rhetoric of Voltairine de Cleyre.” Legacy 20, no. 1/2 (2003): 153–74.

Fernández-Barrial, David. The Haymarket Handbills: Paper as Dynamite. Inside Adams Blog, Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2016/05/the-haymarket-handbills-paper-as-dynamite/.

King, Elizabeth. “Pearl of Anarchy.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/146531/pearl-of-anarchy.

Marsh, Margaret S., 1945. Anarchist Women, 1870-1920. Philadelphia : Temple University Press, 1981.