“First, no woman should say, ‘I am but a woman!’ But a woman! What more can you ask to be?” – Maria Mitchell (1818-1889), American Astronomer

Meteor showers, comets, eclipses, and other celestial events have captured human interest and imagination for thousands of years. Astronomical phenomena have long been speculated over in the press, and curiosity in these phenomena have led us to better understand our world. Throughout history women have played a pivotal role in the field of astronomy and yet have rarely received the recognition they deserve. As in many fields, women’s work has often been eclipsed by their male counterparts or attributed to the institution they were affiliated with. As astronomy became professionalized, women were generally denied the required formal education to be considered a professional astronomer. Whether or not they were able to obtain a degree in the field, women’s stellar contributions to astronomy should not be overlooked. In honor of women’s history month, let’s learn about some lesser-known achievements of women in astronomy throughout the years.

Women have made many important discoveries and historic firsts in the field of astronomy. The first woman known to have discovered a comet was Maria Margarethe Kirch in 1702, but credit was initially given to her husband. Caroline Herschel (Germany) discovered 8 comets between 1786 and 1797, and yet newspapers often described Caroline as her brother’s assistant and argued that she, “had no ambition but to serve him.” The first American of any gender to detect and map a comet was Maria Mitchell in 1847, and the comet came to be known as Miss Mitchell’s Comet. In 1865, Maria Mitchell was appointed as a Professor of Astronomy and the Director of the Vassar College Observatory. One of Mitchell’s assistants at Vassar was Margaretta Palmer, who was later hired by the Yale University Observatory and in 1892 became one of the first women admitted to the Yale Graduate School. The subject of Palmer’s doctoral research was Miss Mitchell’s comet. Women’s ability to practice astronomy professionally grew as more educational institutions began to gradually accept them as workers, scientists and students.

Women at the Observatory

The popularity of the film Hidden Figures drew attention to the women working as computers in the Harvard College Observatory. According to Harvard, the observatory began hiring women around 1875, but there were women who volunteered even earlier. An 1893 article described how Nina (Williamina) Fleming supervised, “…a corps of trained women assistants” at the Harvard Observatory. During her time at Harvard, Fleming discovered many stars and became the first known person to discover a white dwarf. Deaf astronomer Annie Jump Cannon continued Fleming’s work at Harvard of classifying stars, and would go on to record “more than a quarter million twinklers,” or roughly 350,000 stars. Building on the earlier classification work of Fleming, Annie Jump Cannon completed the Harvard Spectral Classification scheme, which was officially adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922 and is still in use today.

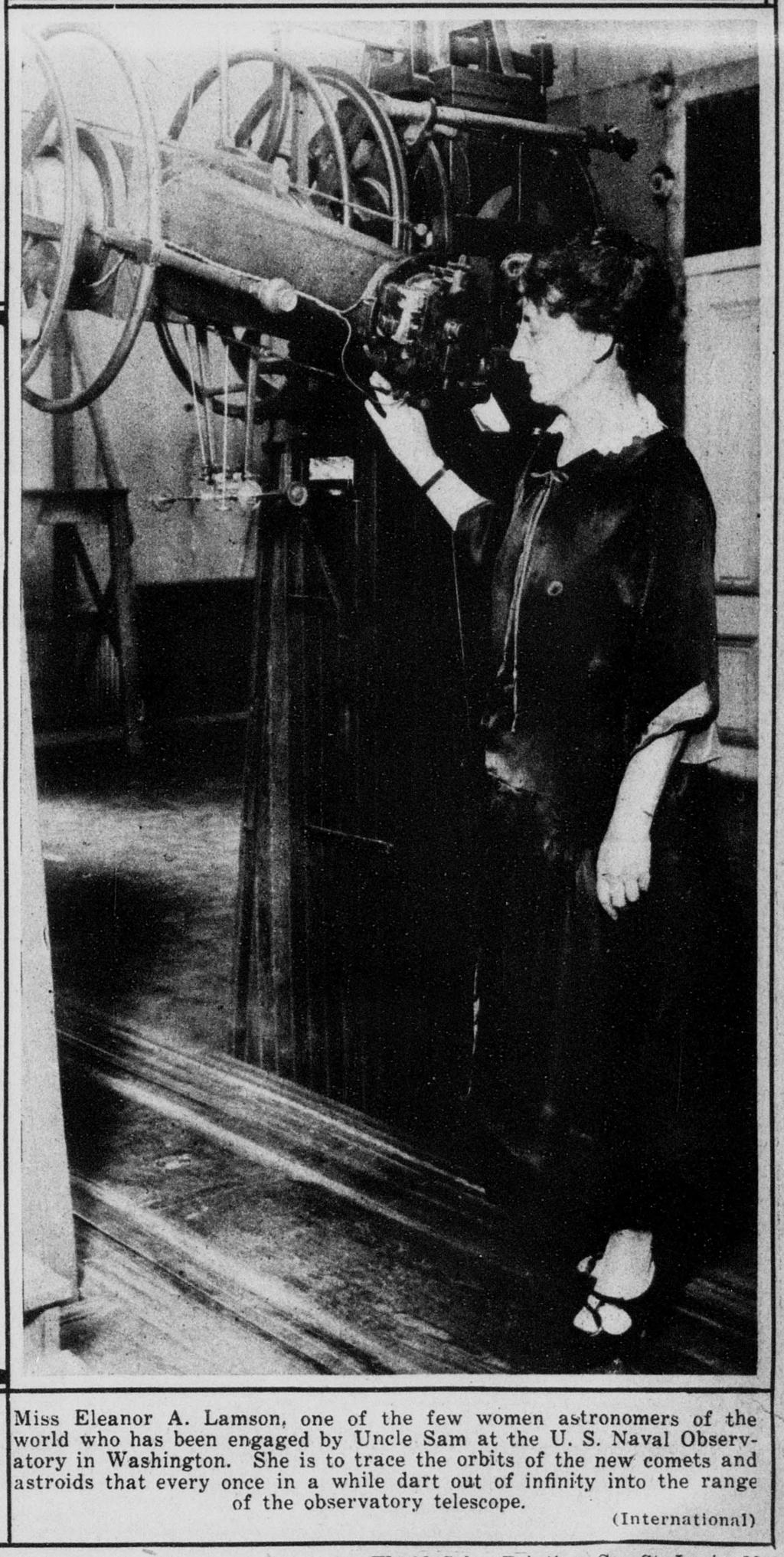

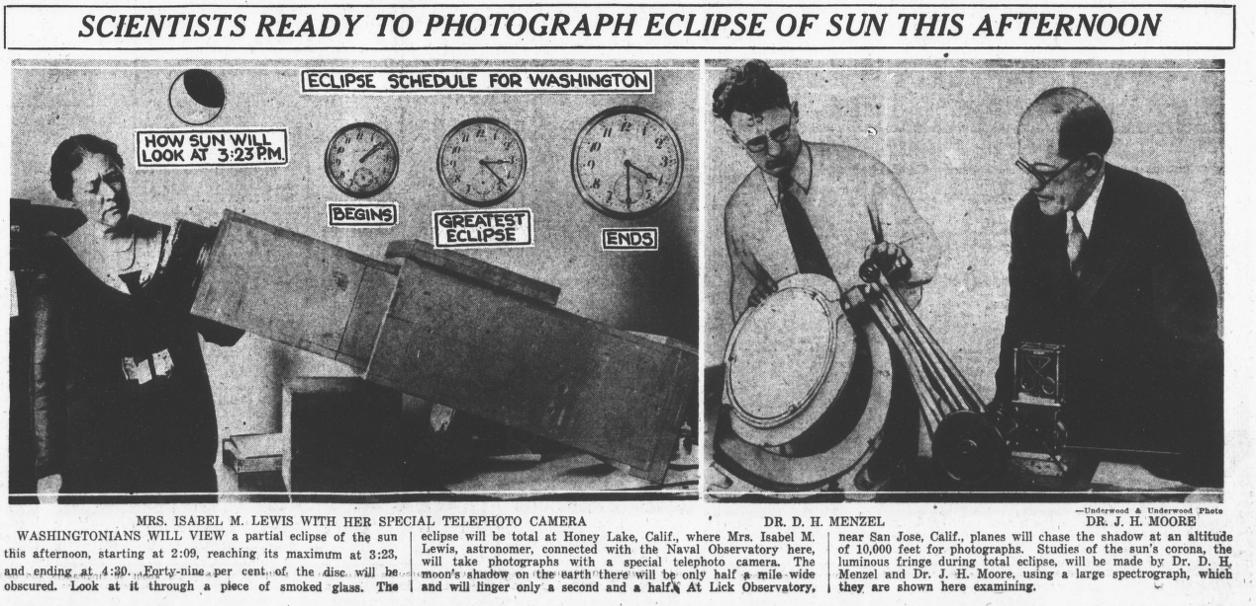

Harvard wasn’t the first or only observatory to employ women. Alice Lamb worked as an assistant astronomer and was partially in charge of the Washburn Observatory in Wisconsin. Dr. Paris Pismis, widely considered the first professional astronomer in Mexico worked at the Tacubaya National Observatory and in 1955 founded the astrophysics program at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The U.S. Naval Observatory hired Isabel M. Lewis and Eleanor A. Lamson long before women were even allowed to enroll at the U.S. Naval Academy.

The Yerkes Observatory employed over one hundred women, and Dr. Nancy Roman conducted research there during her time as a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Nancy would go on to work for NASA and become known as the “Mother of Hubble” for her tireless work in getting approval for the Hubble Telescope to be built. NASA found a way to honor her incredible efforts, and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is currently set to launch in 2027.

Whether they were running an observatory, chasing an eclipse, or simply receiving an education, women in astronomy have defied conventional gender roles to shape and expand the field. Can’t wait for the next celestial event? Why not pass the time by reading “What Science Discovered from the Great Eclipse” by Isabel M. Lewis? We also recommend diving in to Annie Jump Cannon’s series of articles detailing the science behind the total solar eclipse of 1932, Part One, Part Two and Part Three.

Discover more about the history of women in astronomy in historic newspapers on Chronicling America, or get in touch with our librarians and collection specialists via Ask a Librarian.

Explore More:

- Enjoy more Library of Congress Blog posts about astronomy, like Chasing Shadows: Eclipses and Eclipse Observations in the Library of Congress Collections — Inside Adams

- Take a tour of the Maria Mitchell Observatory in the Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey Collection

- Search loc.gov to discover photographs of observatories from all over the world

Sources Consulted:

- Margaretta Palmer ‘1887. Vassar Encyclopedia, Distinguished Alumni.

- Maria Mitchell: America’s First Female Astronomer. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, March 1, 2023.

- Women at the Harvard College Observatory. Wolbach Library, Harvard University.

- Wisconsin at the Frontiers of Astronomy: A History of Innovaiton and Exploration. Peter Susalla and James Lattis, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. NASA.

- Women at Yerkes. University of Chicago.