If you thought that a text was considered heretical, would you print it anyway? What if you lived during the sixteenth century, you were one of the most important printers in Paris, and you were one of the few female printers in the city to own your printing shop? A book in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division suggests that its printer found herself in just this position.

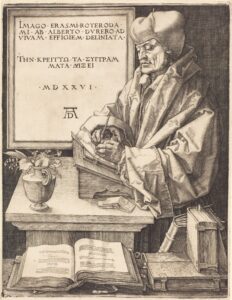

In 1546, Charlotte Guillard (ca. 1485–1557) ran one of the most prestigious printing houses in Paris, the Soleil d’Or (Golden Sun), and that year she printed an impressive, updated edition of the letters of Saint Jerome under her own name. Producing a humanist project in Greek and Latin might have been unusual for most women of her era, but it was not for Charlotte Guillard, who printed many during her career. The editor and commentator of this particular book, however, was the famous Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus (1468?-1536), whose published annotations on Jerome had been censured by the Venetian Inquisition and the Index of the University of Paris two years prior. Why would Guillard choose to publish something that was marked, explicitly, by authorities as problematic for pious Catholics?

A potential answer might be that Erasmus was considered the leading scholar of Jerome’s writing in Europe, and demand for his work was still high enough among the scholars in Guillard’s particular customer base to make the multivolume work profitable in 1546. Located in the printing district of the Quartier Latin near the Sorbonne, the Soleil d’Or was known for specializing in sophisticated religious, legal, and philosophical books. Book historian Beatrice Beech has observed that understanding Guillard’s printing market is important for understanding her contribution to the field of book history:

[Charlotte Guillard] was not part of the French literary scene in that she printed no French romances or poetry and only one edition of the Iliad. Most of her works were in Latin, a few in Greek, with a small scattering of books in French. Nor did she cater to the general religious public with popular religious books such as books of hours or breviaries.

In short, the Soleil d’Or catered to an academic community—a community that excluded female involvement under most circumstances and in which Erasmus of Rotterdam was an influential and increasingly polemical figure.

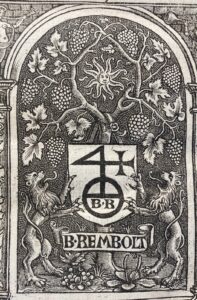

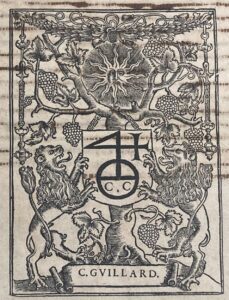

Charlotte Guillard was in an uncommon social position as a female printer and business owner responsible for the production of theological texts during this period of history; however, by 1546, she had been in business a long time and was well-established. She could afford to be a little bold. Guillard had married into the printing business thirty-nine years prior. She had inherited the Soleil d’Or around 1519 after the death of her husband, Berthold Rembolt. She briefly printed under her own name until she married her second husband, Claude Chevallon, probably around 1520. As Chevallon was also a printer, the couple added elements of the Rembolt printer’s device to the Chevallon business mark. When Claude Chevallon died in 1537, Guillard again began printing under her own name. She would print at least 158 editions before her death in 1557.

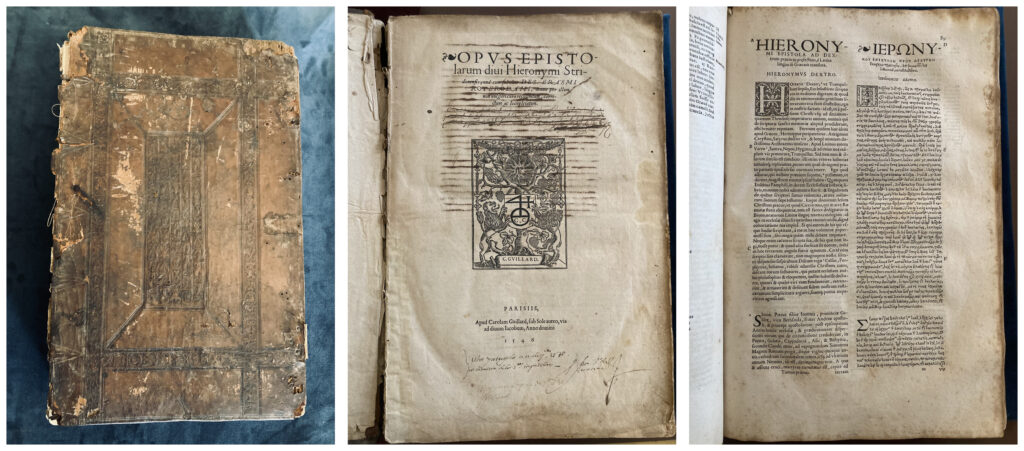

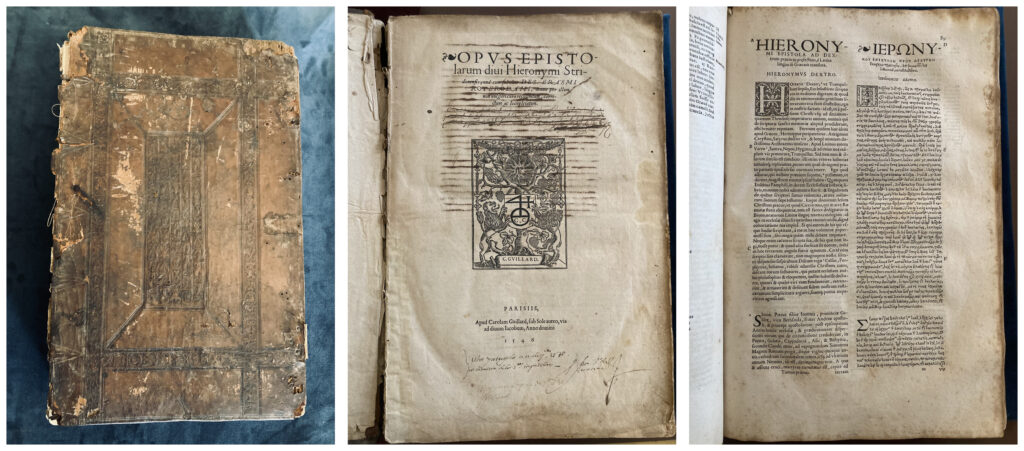

The Rare Book and Special Collection Division’s copy of Erasmus’s edition of Jerome’s letters is one that Guillard printed under her own name. Sadly, this copy is in poor physical condition. The text block has been detached from the boards of the binding, and the the third volume is lacking the final leaves. It is likely that these leaves are absent due to poor treatment and neglect by former owners. Some of the leaves, though, may have been excised intentionally for philosophical reasons.

The missing leaves contain a letter to the reader (candido lectori) from the printing house that mentions the portions of Erasmus’ commentary condemned by ecclesiastical authorities. Though this portion of text is absent from the Library of Congress’ copy, the George Peabody Library in Baltimore has a complete copy, and curatorial staff graciously shared images of the missing text. The letter to the reader warns of Erasmus’ errors and mentions their inclusion in the catalog of censure issued by the Paris theologians. Placed not at the front of the multivolume work but at the back of the third volume (all three bound together in this copy), the location and contents of this letter suggest that Charlotte Guillard and the Soleil d’Or chose to walk a fine line between appeasing the neighboring Parisian theologians while simultaneously honoring a long-standing professional relationship that Claude Chevallon had built with Erasmus and that Guillard had inherited. Being a preferred printer for Erasmus of Rotterdam was no small accomplishment.

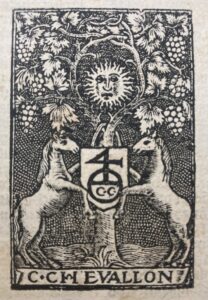

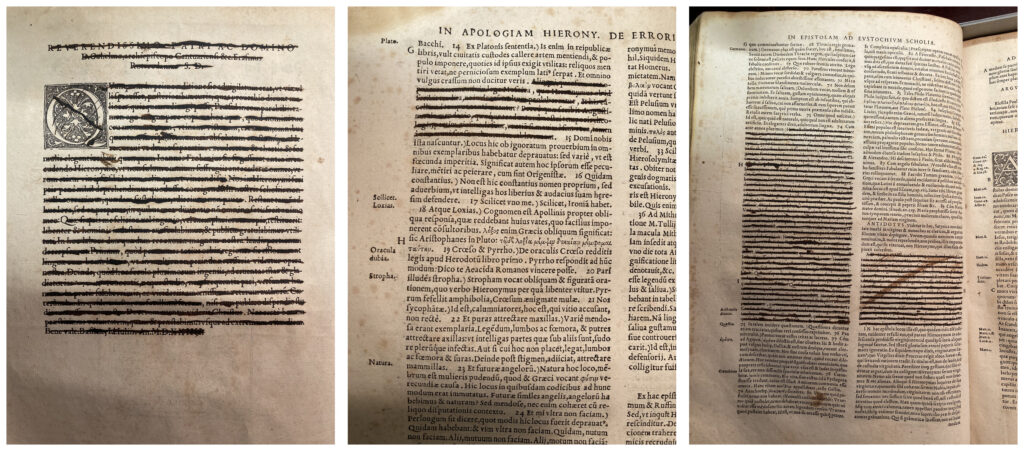

The political winds of post-Reformation Europe did not shift in Erasmus’ favor; his works continued to be censored or banned outright. The copy of his work in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division displays evidence of later systematic censorship in the form of expurgation—the physical removal of parts of a piece of writing that are considered to be harmful, offensive, or, in this case, heretical.

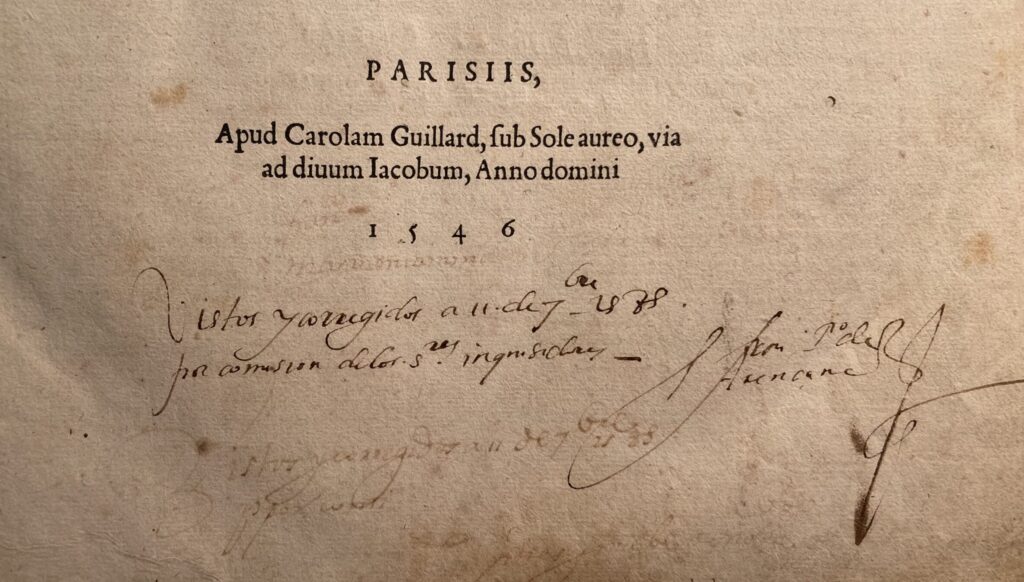

The title page of the first volume indicates that this work underwent expurgation by an official ecclesiastical censor. The inscription beneath the printers statement at the bottom of the page begins “visto y corregido” (inspected and corrected) in 1588.

The expurgated copy at the Library of Congress is in good company. Many copies of texts by Erasmus and other authors suffered similar defacements. The Royal Library in Spain has started a project for banned and expunged books. Copies of Erasmus’ works (including this same 1546 edition printed by Charlotte Guillard) are well-represented in the digital collection.

The physical defacement of the book highlights for contemporary viewers the way that the political tide of the Catholic Counter-Reformation turned against Erasmus, his scholarship, and the humanist methodology that he promoted, but, in 1546 when Charlotte Guillard printed the edition, the history of ecclesiastical censorship against Erasmus was only just beginning to be written. Though the Soleil d’Or printed many of his works, no correspondence from Erasmus and Chevallon or Guillard survive. How did she decide to respond to the political tension? What did she think of her own role in these events? Sometimes the partial stories that we pull from the Library’s vault remain tantalizingly incomplete.

SOURCES

Beech, Beatrice. “Charlotte Guillard: A Sixteenth-Century Business Woman.” Renaissance Quarterly 36.3 (Autumn 1983): 345-367.

Beech, Beatrice Hibbard. “Women Printers in Paris in the Sixteenth Century.” Medieval Prosopography 10.5 (Spring 1998): 75-93.

Broomhall, Susan. “Re-assessing Female Representation in the Print Trades in Sixteenth-Century France.” Parergon 18.2 (Jan 2001): 55-73.

Broomhall, Susan. Women and the Book Trade in Sixteenth-Century France. Burlington, Vt: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2002.

Index de l’Universite de Paris: 1544, 1545, 1547, 1549, 1551, 1556. Edited by J. M. de Bujanda, Francis M. Higman, James K. Farge. Ed. de l’Univ. de Sherbrooke, 1985. Vol. 1. in Index des Livres Interdits. Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada : Centre d’études de la Renaissance, Editions de l’Université de Sherbrooke ; Genève, Suisse : Droz ; Madrid : Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, c1984-2016. p. 179.

Jimenès, Rémi. Charlotte Guillard : Une Femme Imprimeur à la Renaissance. Tours, France : Presses Universitaires François-Rabelais ; Rennes, France : Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2017.

Pabel, Hilmar. “Sixteenth-Century Catholic Criticism of Erasmus’ Edition of St Jerome,” Reformation & Renaissance Review, 6:2 (Jan 2004): 231-262.

White, Eric Marshall and Rebecca Howdeshell. “Heresy and Error” : The Ecclesiastical Censorship of Books 1400–1800. Bridwell Library, Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University, 2010.

RESOURCES

Bridwell Library Special Collections, Southern Methodist University. Heresy and Error: The Ecclesiastical Censorship of Books, 1400-1800. Exhibited September 20 – December 17, 2010.

Hesburgh Libraries, University of Notre Dame. Inquisitio: Manuscript and Print Sources for the Study of Inquisition History. Materials exhibited from the Harley L. McDevitt Inquisition Collection.

Click here to subscribe to Bibliomania and never miss a post!