125 years ago today, the U.S. Senate ratified the Treaty of Paris, officially ending the Spanish-American War and giving the U.S. control over Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. What began as a dispute over a mysterious explosion was inflamed by the American “yellow press,” which pushed for the country to go to war.

The Start of the Yellow Press

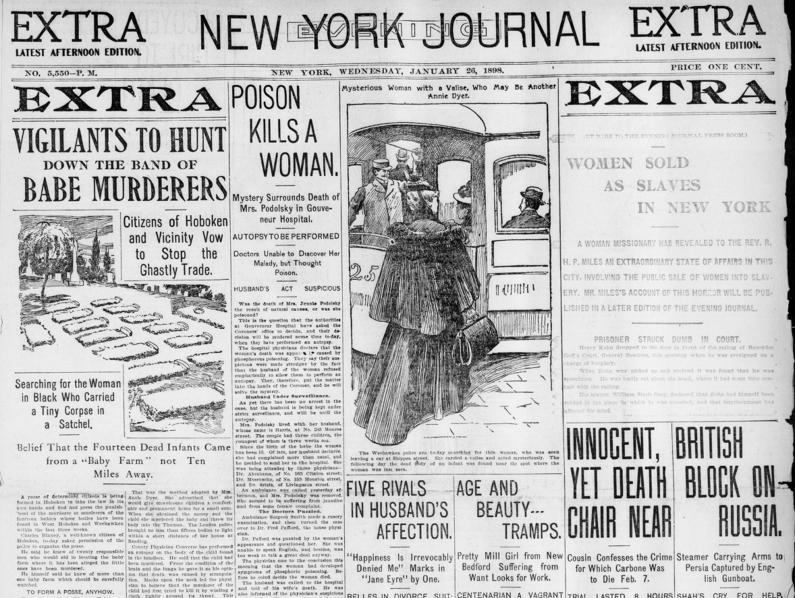

With improvements to printing presses and the invention of the linotype machine, it was easier than ever before to print newspapers by the 1890s. This led to more and more newspapers being published with multiple editions every day. The newspaper market in New York was especially saturated with dailies including the New York Times, the New York Evening Post, the World, and the New York Journal. With fierce competition among them, some papers began looking for ways to stand out.

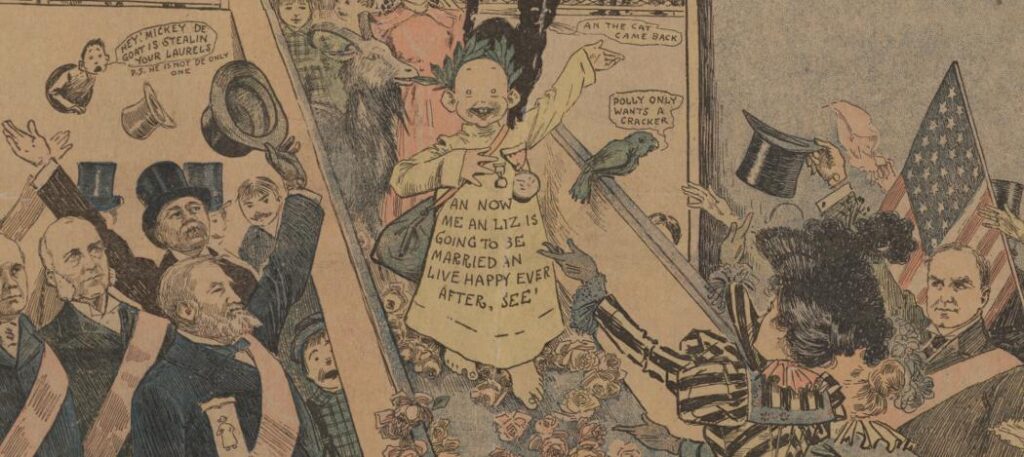

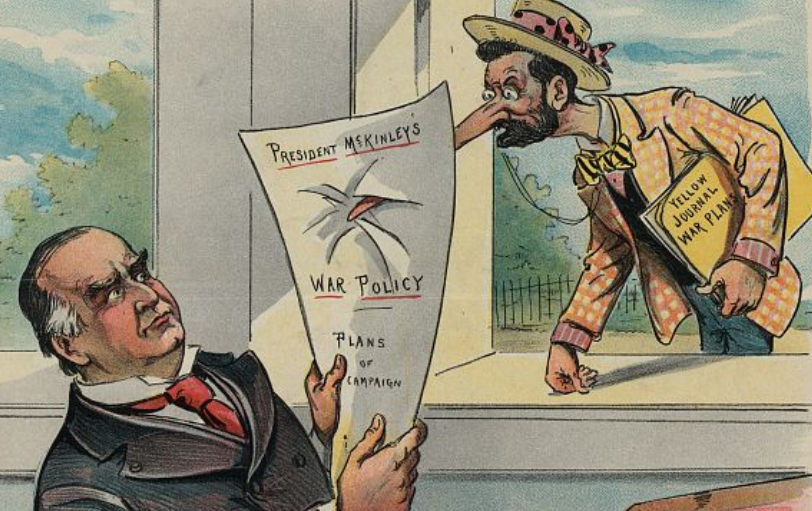

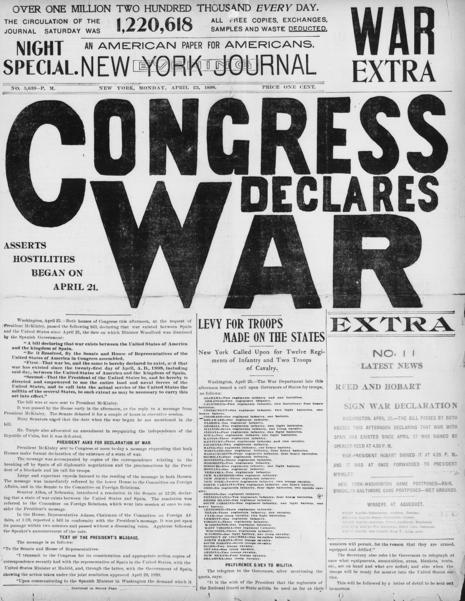

Two publishers in particular are known for their rivalry at that time: Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. Pulitzer purchased the New York World in 1883 and was known for recruiting Nellie Bly and launching a color Sunday supplement in 1895. Hearst purchased the New York Journal in 1895 which began the rivalry with Pulitzer, with Hearst even stealing away the popular Yellow Kid cartoon from the World the following year. As the two pushed for higher circulation numbers, the headlines became bigger and more outrageous.

The term “yellow journalism” began as a reference to Richard F. Outcault’s “Yellow Kid” cartoon. Because it was published in both The World and the New York Journal, “yellow kid journalism” or “yellow journalism” was a way to refer to the sensationalism that they were both known for. The Scranton Tribune questioned if “the American people really do read such trash in newspaper guise as is produced by Hearst, Pulitzer and the other members of the yellow-kid guild.”

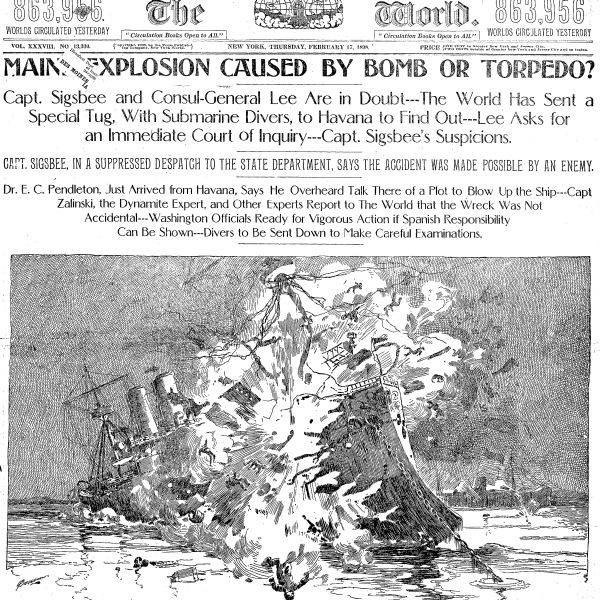

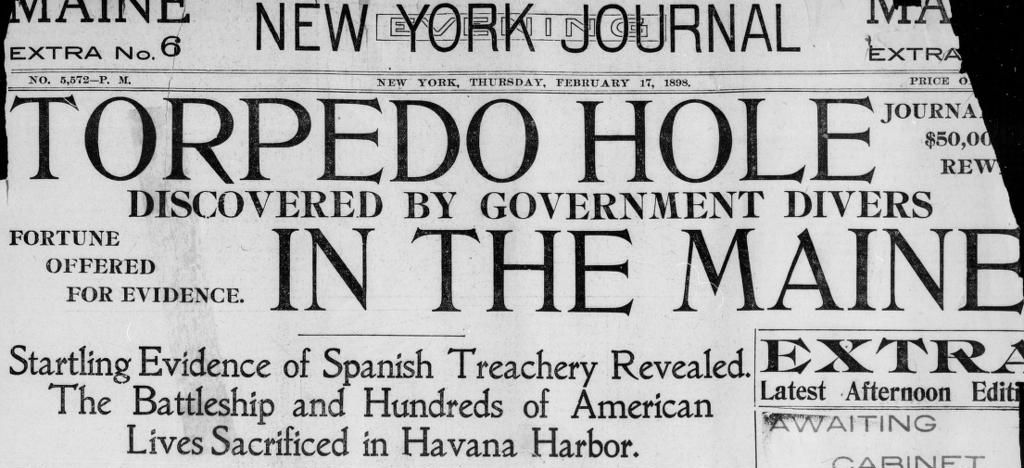

The Sinking of the Maine

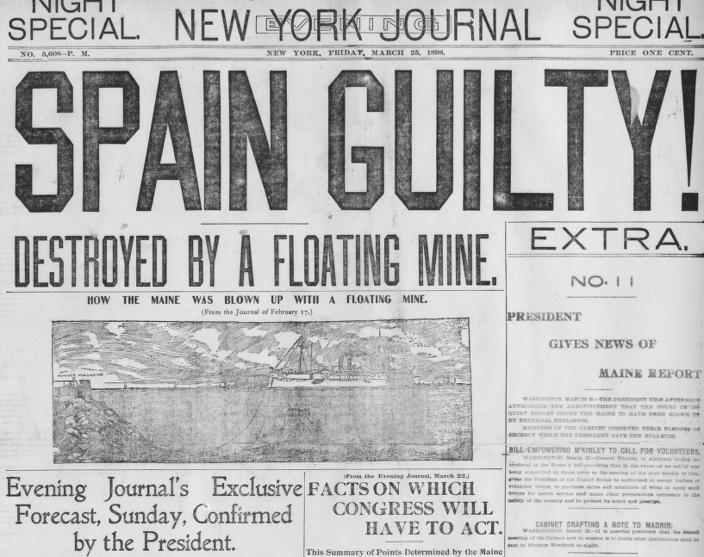

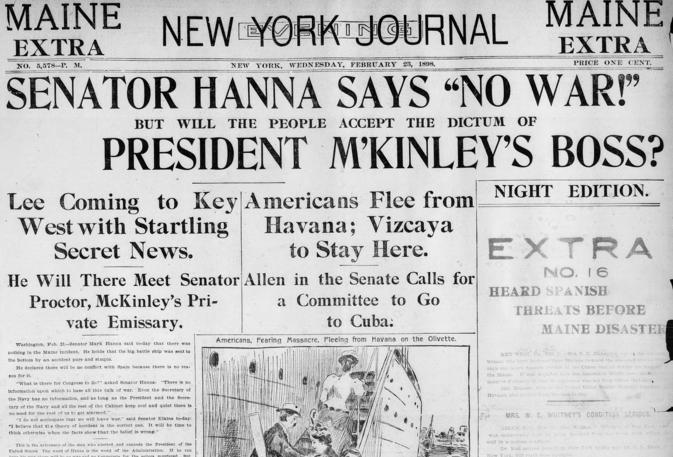

In January 1898 the battleship USS Maine was sent to Havana, Cuba, to watch over American interests during the Cuban uprising against Spain. On the evening of February 15, 1898, an explosion on the Maine caused it to sink in the harbor, killing 266 of the crew on board. Although the exact cause of the explosion is still unknown, within days of the explosion, newspapers were blaming Spain. Evidence was misreported or even fabricated, published with large headlines and gruesome images, shocking readers.

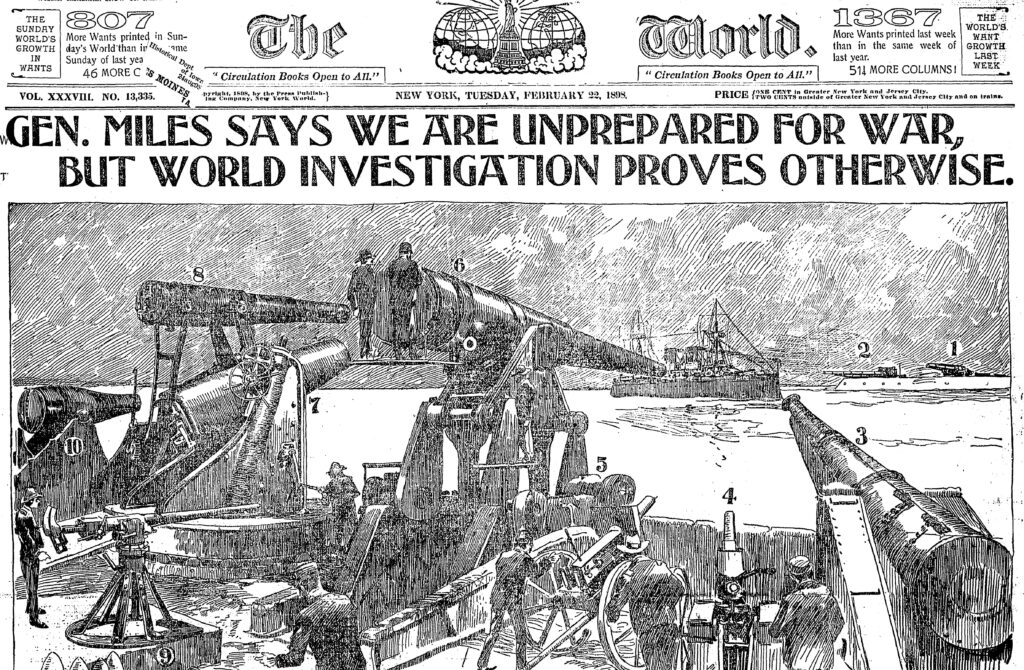

Once the blame was laid onto Spain, headlines in newspapers including the New York Journal and the World began calling for action. They even went as far as goading President William McKinley and the U.S. military to try and force a military response.

Other newspapers and magazines of the time noted the rivalry between Pulitzer and Hearst and openly commented about their influence on the war. The San Franscico Call satirically noted the “prompt and able fashion in which Hearst and Pulitzer took charge of the Government at a critical period.” The New York Times wrote a scathing editorial on March 1, 1898, about the “shameless public lying” in the “yellow journals,” even suggesting that they should be suppressed: “It would be criminal negligence for the authorities to permit the public sale of the dangerous literary explosives which the yellow journals make and vend.”

Coverage of the War

Congress and President McKinley sent an ultimatum to Spain to withdraw from Cuba on April 20, 1898. From there things moved quickly as Spain severed diplomatic ties the next day and then declared war on the U.S. on April 23. Newspapers continued to cover the war with large headlines and exaggerated patriotic imagery. The Indianapolis Journal in explaining “Our Yellow Journals” described how a “war extra” edition of a newspaper should be made: “The recipe for making a war extra is to get a line of fact or rumor and charge it with the carbonic acid gas of imagination until it fills three columns, half made up of headlines in poster type.”

Conflict spread from Cuba into Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam. The war did not last long, however, and a peace protocol was agreed to on August 12, with the treaty signed on December 10 and ratified February 6, 1899.

Yellow Journalism Today

Yellow journalism and the sensational headlines of the Journal and the World raged into the early 1900s, but eventually people began to mistrust what they read. This led some newspapers to go in the opposite direction, emphasizing that their reporting was “unbiased” and fact-based. The New York Times set itself apart from its competitors in 1897, introducing their slogan “All the News That’s Fit to Print” on February 10, 1897, which they still use today.

Now the terms “yellow press” and “yellow journalism” have entered the vernacular and refer to sensational reporting, where facts have not been checked and may be grossly exaggerated. New terms such as “fake news” and “clickbait” have become popular to describe some of the exaggerated and poorly researched articles that can be found online. Does this mean that we have entered into a new era of yellow journalism?

Additional Resources:

- Sinking of the Maine: Topics in Chronicling America

- Spanish-American War: Topics in Chronicling America

- Yellow Journalism: Topics in Chronicling America

- Today in History – February 15: Remember the Maine!

- New York Journal and Related Titles, 1896 to 1899

- Find additional articles about the Spanish American War, yellow journalism, Pulitzer, Hearst, and more in Chronicling America.*

* The Chronicling America historic newspapers online collection is a product of the National Digital Newspaper Program and jointly sponsored by the Library and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Follow Chronicling America on X @ChronAmLOC

Click here to subscribe to Headlines & Heroes–it’s free!