This is a guest post by Lena Denis, reference librarian in the Geography and Map Division.

Growing up in a Brazilian-American household, I’ve long appreciated the delicious versatility of the Atlantic cod, scientific name Gadus morhua, known to the Portuguese-speaking world as bacalhau in its preferred salted and dried form. It was only when I began working as a map librarian, however, that I saw how powerful cod truly was. Centuries before my family started serving it for holiday meals, European fishing boats traveled all the way to the edge of the world (as they knew it), searching for cod fishing grounds and mapping the unfamiliar coastline along the way. Eventually their maps would be seen in Europe, spreading the news of a plentiful “Land of Cod” and many other curious details of a new continent that they began calling “America.”

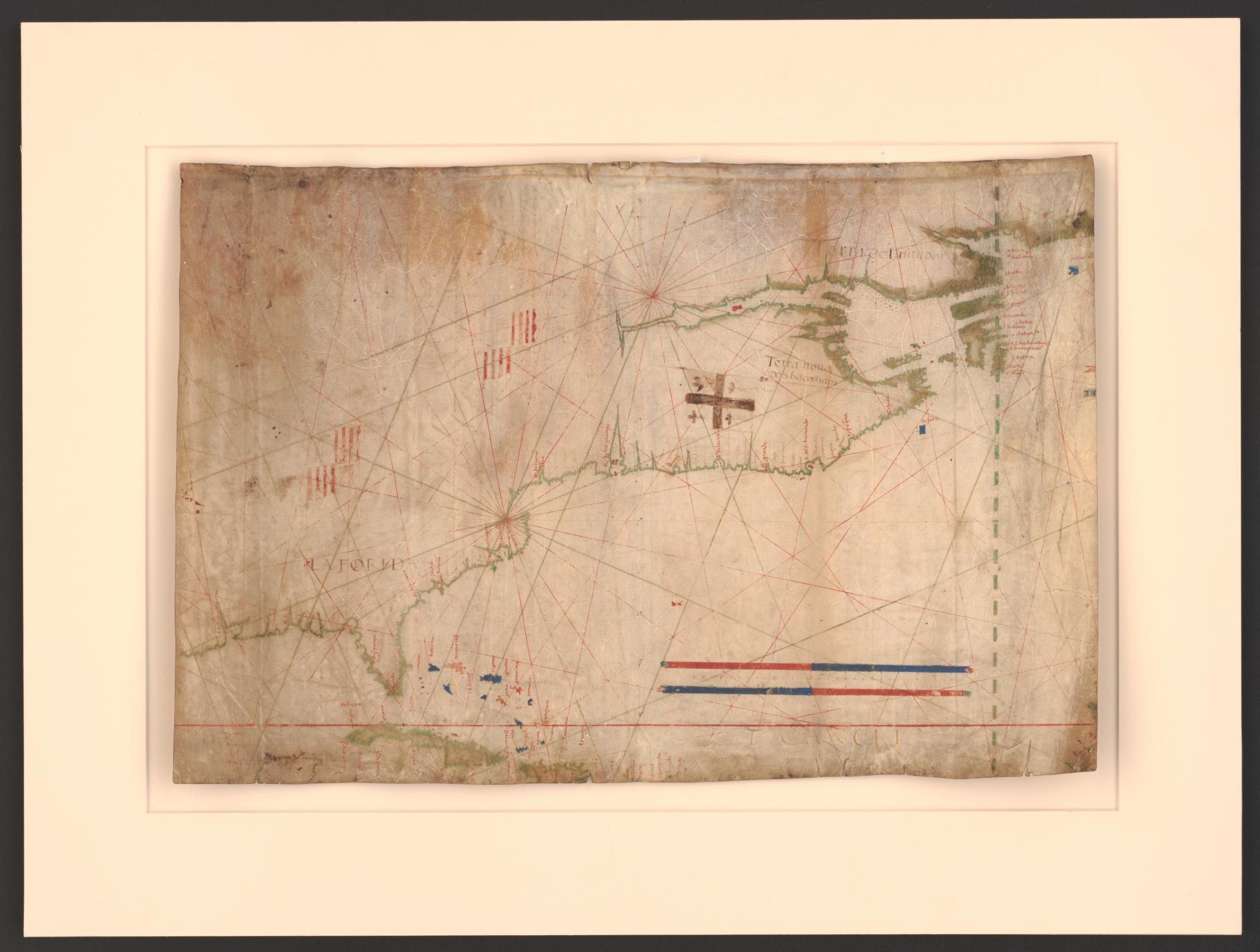

Some of the earliest maps in the Geography and Map Division are manuscript (hand-drawn) maps on vellum (animal skin), rather than printed on paper. A subset of these maps in the collection, called portolan charts, are early maritime navigation aids made by Mediterranean sailors of various nations from roughly the 14th through 18th centuries. Some portolan charts are very spare in detail, with spindly lines for coastal features and nothing else, but some are packed with images and descriptive names. One Portuguese chart from 1560 shows a relatively modest coastline stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to Newfoundland and Labrador, punctuated inland by flags of European claimants, but dotted with the names of towns, settlements, and features in small text all along that coast. The most noticeable features on the map are the flags and the mapmaker’s names for the regions: La Florida, Terra do lavrador (Labrador), and Terra nova dos bacalhaos, or “New land of cod.” (“Terra nova” stuck around, becoming the English name “Newfoundland.”)

One of the many intriguing features of Portuguese portolan charts specifically is that several famous examples were considered state secrets, so that no other state-sponsored navies or independent merchants could poach the information for financial or military gain that the Portuguese had gathered during their exploration. However, the secret about Terra nova dos bacalhaos was already out by the time this map was made. The French and English had learned about it from their own explorers in the early 16th century, and would one day battle to colonize this area, the future country of Canada.

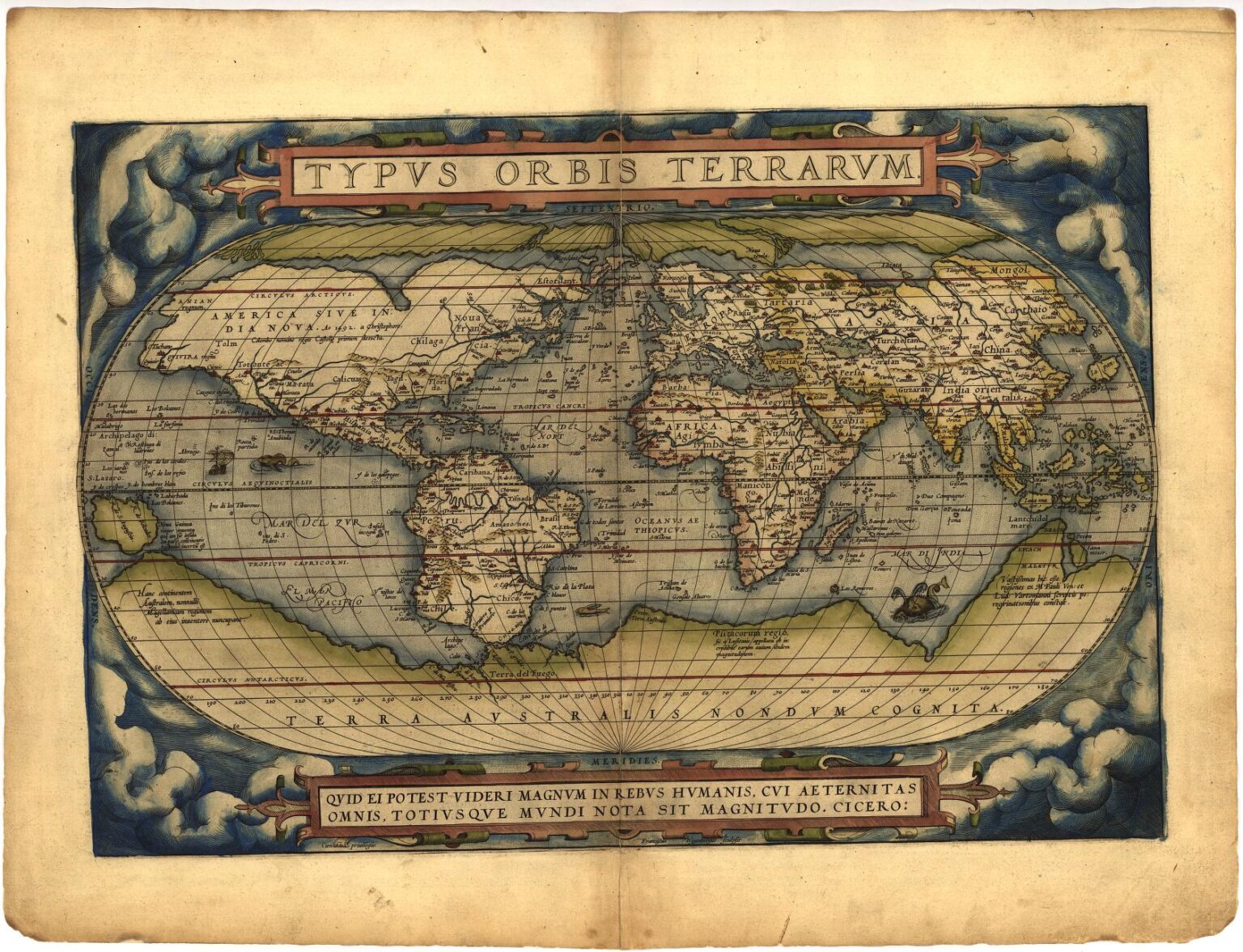

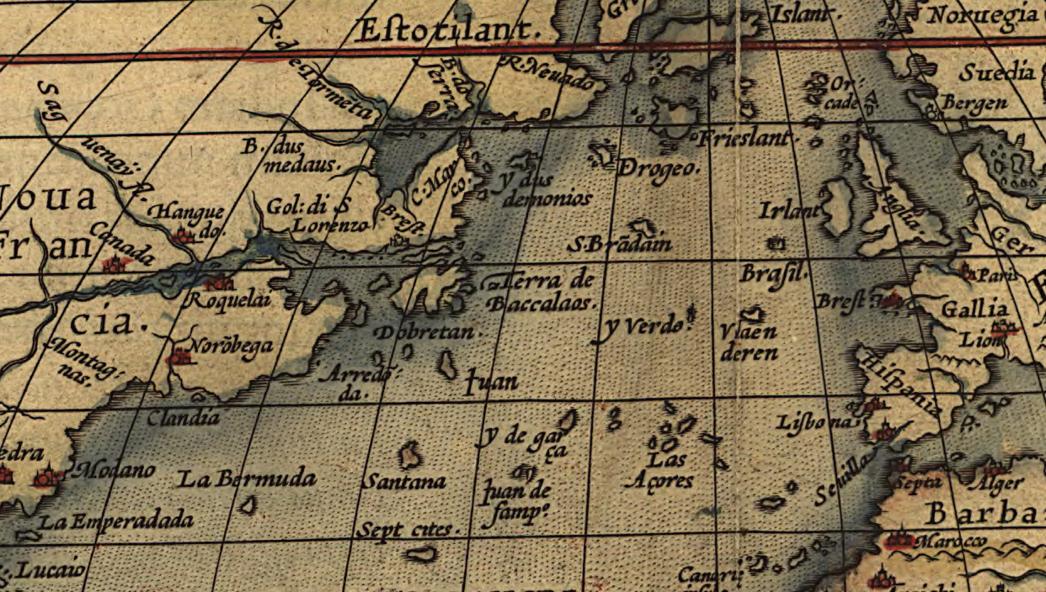

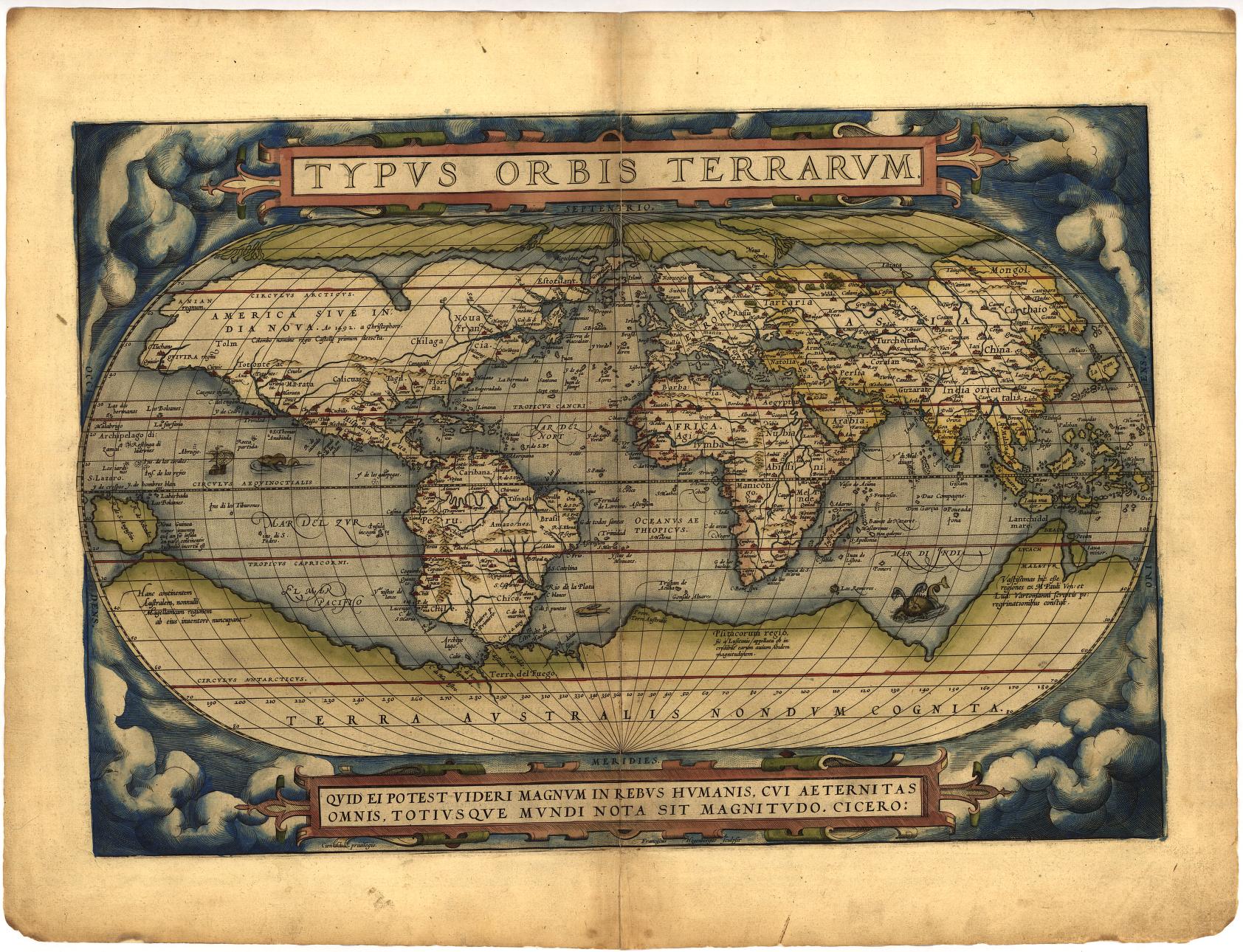

Cod had hit the big-time back in Europe, feeding the appetites of the wealthy and not just the pockets of fishermen. It was so beloved that it soon appeared on a world map in one of the most famous atlases ever made, Abraham Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, which is also widely considered by cartographic historians to be the first atlas. The Geography and Map Division holds a full-color first edition from 1570. The world map contains a lot of information, including some eye-catching details like sea monsters, but if you look carefully at the text, you’ll see a reference to cod off the coast of what is now Newfoundland and Labrador. The map text is mainly in Latin, with a mix of words from other languages thrown in for terms that were hard to Latinize, so “Land of Cod” appears on the map as “Terra de Baccalaos.”

Bacalao is the modern Spanish word for cod, but as the atlas and the portolan chart show, many variations in spelling can be found for this fish on early European maps. As Mark Kurlansky described in his 1999 seminal book, Cod, the origins of the word “cod” in English and of the words for it in other languages are not clear, although many theories exist (35-37). The word I use most for it, bacalhau, probably comes from the same origin as the Spanish word bacalao and Italian word baccalà, potentially an ancestral word in Basque or Catalan, which were the languages of the first known Iberian fishermen to go all the way to modern Canada searching for cod. Whatever the origin of the name(s), and whatever the individual nations called it, the point remains: cod moved people, physically as well as emotionally. Over the following centuries, ship loads of Europeans migrated to the Americas for the chance to fish for cod, eventually establishing the need for treaties, fishing grounds rights, and regulations to protect supply.

Eventually, all those legally binding fishing grounds demarcations would become sticking points for a new political entity: the independent United States of America.

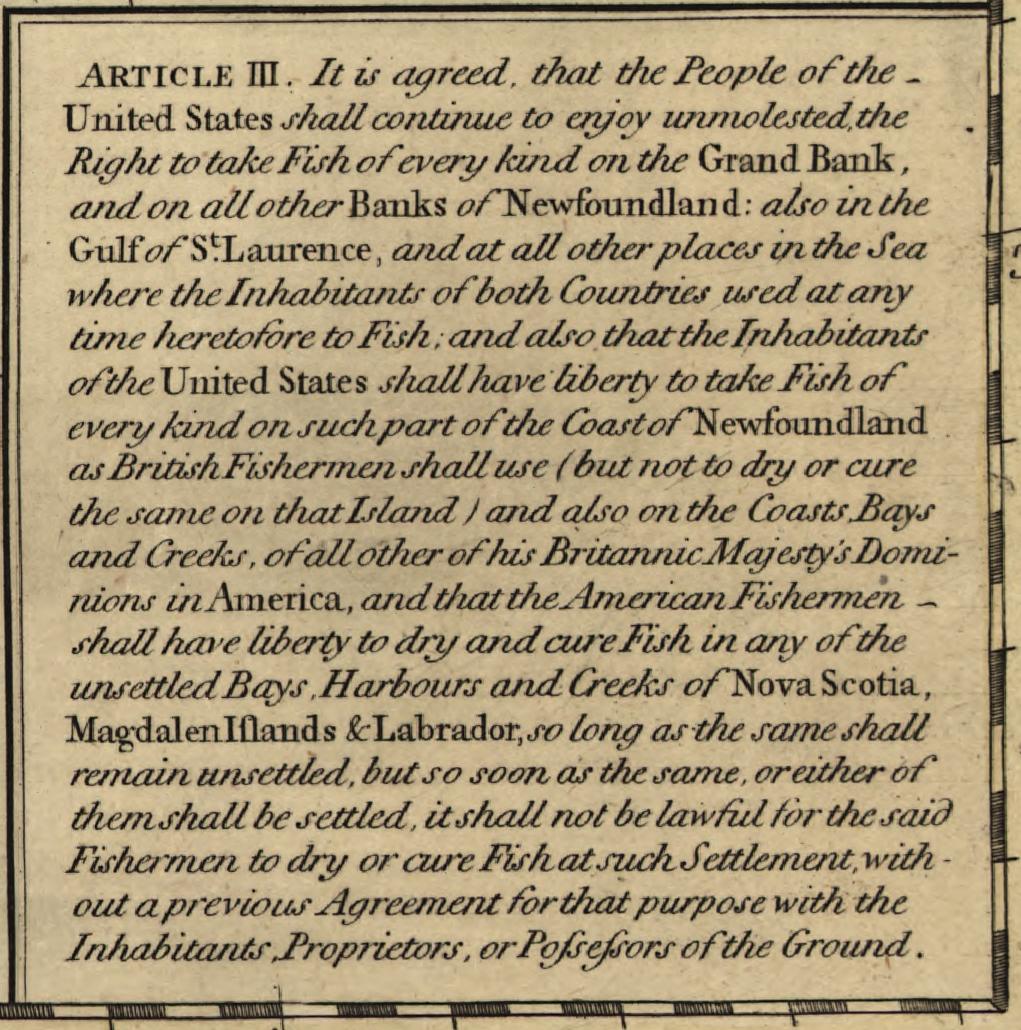

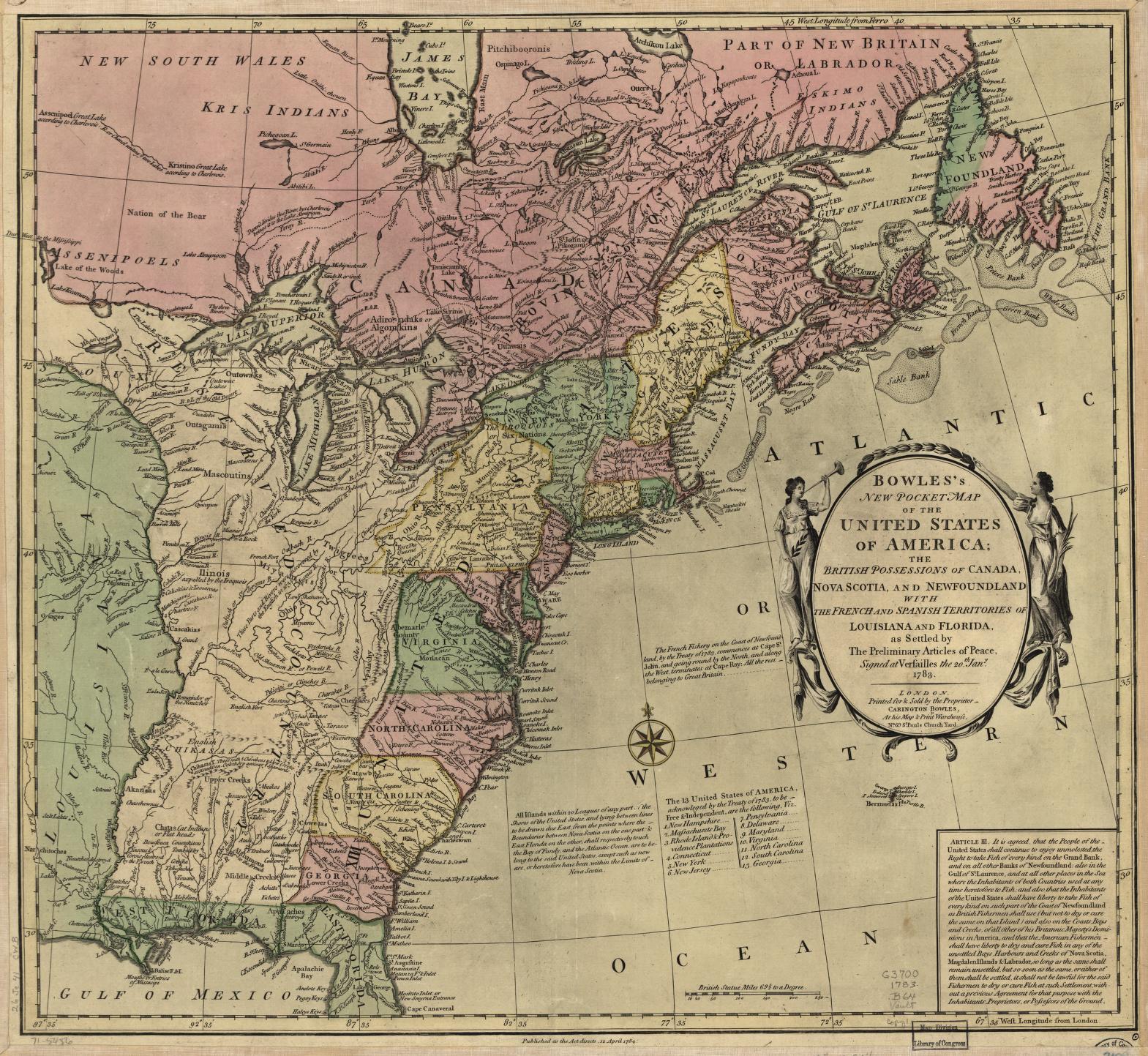

The colonies of New England in particular had become fabulously wealthy from cod fishing over the 17th century, and during the peace process after the American Revolution, the nascent USA took a hard stance on securing cod-based future wealth while negotiating the 1783 Treaty of Paris. Article Three of the treaty was all about fishing, beginning with the statement, “It is agreed that the People of the United States shall continue to enjoy unmolested the Right to take Fish of every kind on the Grand Bank and on all the other Banks of Newfoundland, also in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and at all other Places in the Sea, where the Inhabitants of both Countries used at any time heretofore to fish…”

After the treaty’s successful ratification, securing American independence and peace with Great Britain, the news about the fishing grounds was made known to the public through a variety of ways, including informative maps for British as well as American audiences. The Geography and Map Division has several copies of one of the very first maps to refer to the former colonies as the “13 United States of America.” Significant though this new nomenclature is, the detail most interesting for our purposes is that the publisher focused extensively on Article Three, reprinting it in full on the lower right corner of the map and noting around the geographic fishing areas who had control of them. Past differences aside, Great Britain and the new United States were going to have to learn to get along amicably when it came to the all-important business of cod.

In the United States, celebrating cod would remain a national pastime, as its importance to the development of the country could never be forgotten, especially in New England where access to the Newfoundland cod fisheries was now a guaranteed right. A statue of a cod, later nicknamed the Sacred Cod, still hangs to this day in the House of Representatives at the Massachusetts State House. You can read more about it through another digitized item from the Library of Congress, A History of the Emblem of the Codfish in the Hall of the House of Representatives, comp. by a committee of the House.

Source: https://blogs.loc.gov/maps/2024/05/in-cod-we-trust/